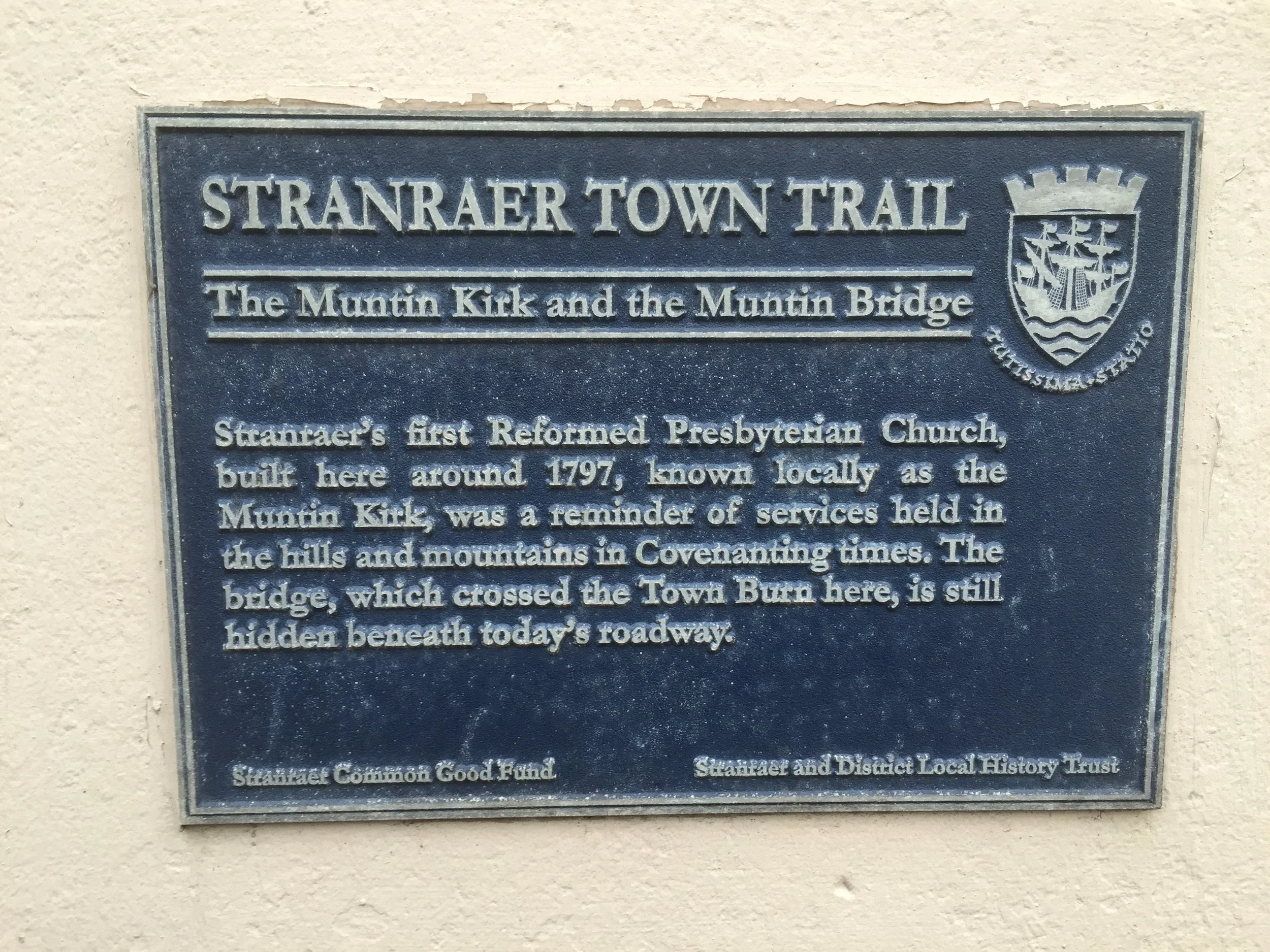

Our church building features on the Stranraer Town Trail, which highlights 19 places of interest in Stranraer. The blue plaque, on the front well of the building, notes that when the original RP church building in Stranraer was built around 1797, it was known locally as the Muntin (Mountain) Kirk as a reminder of services held in the hills and mountains in Covenanting times.

An accompanying leaflet, produced by the Stranraer & District Local History Trust, says:

“The R. P. Church was built in 1825. Once known locally as the Muntin’ Kirk, it is a reminder of the days when members met in secret in the hills to avoid religious persecution. Beneath the modern road are the old ‘Mountain Bridge’ and another culverted stretch of the town burn.”

The first place of interest on the leaflet is the Castle of St John: “In 1678 it was used as a base by John Graham of Claverhouse — Bluidy Clavers — and his troops during their pursuit and suppression of local Covenanters”.

Other places of interest included are North Strand Street, Burnfoot, North West Castle, the Garden of Friendship, the Stranraer Distillery, McCullouch’s Mill, Tradeston, Little Ireland, New Town Hall, McWilliam’s Pump, Dunbae House, the Old Parish Church, the Old Town Hall, the Princess Victoria monument, the West Pier, George Street, and Jubilee Fountain.

The following history of Stranraer is included on the leaflet:

“The place-name Stranraer is thought to mean the row of houses on the strand or shore. Alternatively the name could be a combination of the Gaelic words struathan and reamhar and means the fat stream' or the 'place where the shoals of fish are to be found'.

The town of Stranraer came into being late in the Middle Ages. Around 1510 the Adairs, a powerful local family, built a massive stone castle which was both a family home and an administrative centre for their estates. Stranraer grew up in the shadow of the castle. It became a Burgh of the Barony in 1595 and in 1617 was elevated to a Royal Burgh by James Vl.

By the late 18th century Stranraer was the largest town in Wigtownshire. Its economy was based on tanning, fishing, boat building and linen weaving and it acted as the market centre for the western part of the county. Potatoes and grain were exported to Ireland and huge quantities of timber were imported from the Baltic and later Canada.

In the early 19th century Stranraer was a moderately prosperous place but further development was hampered by the town's geographical isolation. That was to change in 1861 when the railway came to town. The following year work was completed on the new East Pier and in 1872 the iron paddle-steamer 'Princess Louise' inaugurated the ferry service to Larne. Stranraer now had good rail contacts with Glasgow, central Scotland and the north of England and, more importantly, had become the principal ferry port between Scotland and Ireland.”