Stephen recently wrote an article for Gentle Reformation entitled ‘Serving God in Unglamorous Places’. You can read it here. Both that article and an article written a few days later (just prior to the death of Tim Keller), were featured on the website Challies.com. We trust they will be an encouragement to you.

Not My King?

It was revealed last week that the Queen’s funeral cost the government an estimated £162 million. The cost of the Coronation has not yet been calculated, but it is estimated to have been £50-£100 million. That’s just one of the reasons why the hashtag #NotMyKing was trending in the lead-up to the big event. As much as I have my reservations about our new king however, slogans and protests don’t change the fact that Charles III is now our monarch. A recent Guardian cartoon made a similar point in the wake of reports that global temperatures were heading towards ‘unchartered territory’. The drawing is of the earth with a sign stuck in it saying ‘Not my planet’. But for better or worse this is our planet – and Charles is our king.

In a way it reminds me of what the Bible says about a far greater king – Jesus Christ. Indeed, the whole Coronation service is designed to remind us that there is a greater king than the one being crowned. As the new monarch is given the orb he is told ‘remember always that the kingdoms of this world are become the kingdom of our God, and of his Christ’.

Just as King Charles was anointed, so was Jesus. ‘Christ’ is not a surname; like ‘Messiah’ it simply means anointed. Jesus is the Messiah, the Christ – he’s God’s anointed. As the Archbishop of Canterbury prayed at the Coronation: ‘Thy prophets of old anointed priests and kings to serve in thy name, and in the fullness of time thine only Son was anointed by the Holy Spirit to be the Christ’. This was prophesied long before Jesus’ birth in the likes of Psalm 2, where God says ‘As for me, I have set my King on Zion, my holy hill’. Elsewhere in the psalm he is called God’s ‘Son’ and his ‘Anointed’.

On one level a psalm like that could be understood as speaking of a human king, like the Biblical King David. But the language is far too exalted to describe any mere human being, as the Apostles realised when they quoted its language in reference to Jesus’ crucifixion (Acts 4:25-26).

And there’s the rub. The Christ was long-expected – but quickly rejected. Jesus’ friend Martha once told him: ‘I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, who is coming into the world’. But though he was expected, when he came, he was crucified.

How did the world react to their King? It reacted, and still reacts, just as Psalm 2 predicted: ‘the nations rage…the kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD and against his Anointed’.

In other words, the world – including each of us by nature – respond with the hashtag #NotMyKing. Jesus’ rule looks restrictive. We believe the whispers that to follow him would conflict with human flourishing. And so we say of the LORD and his Anointed: ‘Let us burst their bonds apart and cast away their cords from us’.

How does the psalm tell us that God reacts to this? By wringing his hands? Not at all: ‘he who sits in the heavens laughs; the Lord holds them in derision’. How we react at the enthronement of a king says more about us than it does about the king.

Last month, as Charles and Camilla visited Merseyside, the BBC shared a video of protestors chanting ‘not my King’ being drowned out by children chanting ‘he’s our king’.

Protestors chanting “not my King” are drowned out by children chanting “he’s our King” pic.twitter.com/1YrEPoeb8C

— BBC Radio Merseyside (@bbcmerseyside) April 26, 2023

It was remarkably similar to a prediction in another psalm that even if God’s anointed king is rejected by the sophisticated of the world, children will worship him: ‘Out of the mouth of babies and infants, you have established strength because of your foes, to still the enemy and the avenger.’ (Psalm 8:2). Jesus quoted that very verse to the religious leaders of his day when they complained about children praising him.

The coronation of an earthly king is designed to point us to a greater King. One man who realised this at the Coronation of William IV in 1831 was the Reformed Presbyterian minister Thomas Houston. William IV, who was crowned at the age of 64, was the oldest person to assume the monarchy until Charles III. On the morning of his Coronation, Houston wrote in his journal:

‘Today, the King of these nations will be crowned, and many will be anxious to testify to him their affection and loyalty. Let me ever bear faithful allegiance to Messiah the Prince of the kings of the earth.’

Published in the Stranraer & Wigtownshire Free Press, 1 June 2023

Organisation of a congregation in The Gambia

For the last few months, Stephen has served as Interim Moderator of a new work in Brikama, The Gambia. That role will come to an end with ordination of Sylvester Konteh tomorrow. Sylvester’s ordination and the organisation of the congregation will, God-willing, be available to watch via livestream. The details are as follows:

Our interim elder, Rev. Peter Loughridge (North Edinburgh), along with Rev. Stephen McCollum (Airdrie) are in The Gambia to take part in the ordination

“On Saturday 13th May 2023 at 6pm UK time (5pm Gambia time/Greenwich Mean Time), the ordination of Sylvester Konteh and organisation of Brikama RPCS will take place. The service will be live-streamed via a Zoom webinar. To watch, click on the link below. You do not have to have Zoom to watch, but you will be asked to leave your name and email address.Here is the link:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89212436197

Please be aware that this attempted live broadcast via Zoom may not be successful due to internet issues and/or sound issues at the venue. We apologise in advance if that is the case! A cameraman will be present at the event to produce an official video which will be uploaded to YouTube at a later date. We will send that YouTube link out when it is ready.”

An emergency alert some still haven't heard

Ten days ago, some of us received a test alert from the government’s new nationwide emergency alarm system. Others are still waiting, and hoping the teething problems are ironed out before we need warned about a real emergency. Other countries have had such alert systems in place for a long time – my in-laws in Canada regularly get pinged about incoming tornadoes or snowstorms. It remains to be seen how frequently such alerts will be used here in the UK where the weather isn’t quite so extreme.

Long before we had the technology to warn people of danger via their mobile phones, some attempted to do the same with books. The most famous – and one which has never been out of print since it was first published in 1677 – is Joseph Alleine’s ‘An Alarm to the Unconverted’. Also published as ‘A Sure Guide to Heaven’, at one time Alleine’s book outsold every other book published in English other than the Bible.

As the title suggests, Alleine’s book is not warning about a physical danger, but about a spiritual one. It is aimed at those who call themselves Christians but have not experienced what the Bible calls ‘conversion’ (Acts 15:3), or to use the words of Jesus, have not been ‘born again’ (John 3:7). Alleine did not expect his message to be popular, explaining to his readers, ‘I am not fishing for your applause, but for your souls – my work is not to please you, but to save you’.

It might be expected that such a book would only be aimed at those in the pew, but remarkably there have been famous ministers in the history of the church who only realised they were unconverted after their ordination. Thomas Scott (1742-1821) is known for his famous Bible commentary, an edited version of which was published as a ‘Study Bible’ by former Stranraer minister William Symington in the mid-1800s. Scott became a minister as a way to earn a living after his plan to become a surgeon failed, and he realised that his father was going to leave the farm he had been working on to his brother. His conversion came later, through the influence of his ministerial colleague John Newton, the former slave-trader who became an abolitionist and wrote ‘Amazing Grace’. Scott describes his experience in his autobiography, ‘The Force of Truth’.

Here in Scotland, Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847), one of the founders of the Free Church of Scotland, was appointed as a minister because of family connections, and spent most of his time lecturing on mathematics and chemistry at the University of St Andrews. Although censured by his local presbytery for neglecting his parish, he was unrepentant, arguing that a minister’s duties consisted of little more than preaching on Sunday, leaving the remainder of the week for whatever scholarly or scientific interests he wished to pursue. Unsurprisingly, attendance at his church declined!

One winter however he became dangerously ill and began reading the works of evangelicals, such as the abolitionist William Wilberforce and, ironically, Thomas Scott. Chalmers was soon converted and his parish ministry transformed. He then moved to Glasgow where his ministry had a huge impact on many who had been consigned to poverty by rapid industrialisation and urbanisation.

In America, the Irish immigrant Gilbert Tennant made it his mission to awake his fellow Presbyterians from their spiritual stupor, and preached an infamous sermon entitled ‘The danger of an unconverted ministry’. Then as now, it couldn’t be assumed that those standing in a pulpit actually believed Jesus’ teaching.

The great danger of unconverted ministers is that it leaves the people in the pews unlikely to believe a gospel they never hear. They assume that being a Christian simply involves attending church and trying to live a good life – and are never told anything to the contrary.

Imagine the anger there would be if our new alert system wasn’t used in a time of real danger. Or if technical problems meant that those who could have been saved by an alert never received the message. To have information about an imminent danger and not alert people would be a serious thing.

Joseph Alleine wrote his book to ensure that no-one in his day could say that they hadn’t been warned. And all these years later, it’s not too late to hear and respond to his alarm. Which is, of course, simply the alarm sounded by the prophets, the apostles and Jesus himself: ‘Unless you repent, you will all likewise perish’ (Luke 13:5).

Published in the Stranraer & Wigtownshire Free Press, 4th May 2023

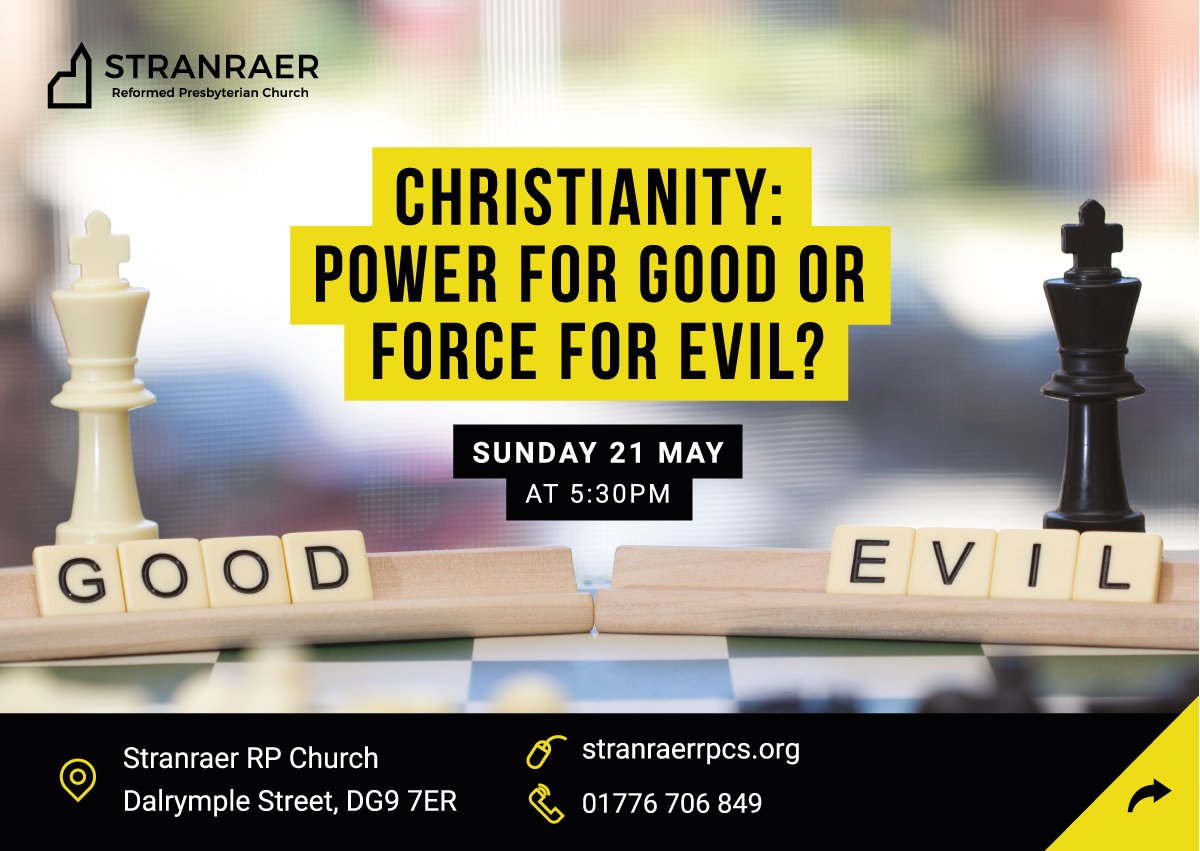

Special Services: 21 May

We are planning to hold two special services on Sunday 21st May. As a congregation, we are taking it as an opportunity to invite friends who don’t normally come to church. All the details are below and visitors will be particularly welcome!